Lyra Garcellano, the World, and the Artworld

Some artworks need only to be looked at, while others need to be thought about. But there are a select few that are best coupled with a poem. Such are many of Lyra Garcellano’s works that she once composed an ekphrastic poem to accompany her work. Among the array of works deserving this, her Trapdoor I surely demands one.

Upon thin flesh fall mountains and hills,

Needles and pins strike to the bone.

A moment’s rest, then sudden chills—

Screeching thoughts say: “You’re alone.”

Unjustly bestowed this uneven corpse;

Creases are valleys, folds are waves.

Should I throw it around till it drops?

Time will stand still before it caves.

This unhappy life captured within a frame,

Beyond life’s frame a frame so hideous.

What life would be if I could only tame

My own figure to appear so glorious.

No one sees me beyond this absurd body

Self equated to flesh, flesh equated to self

Some say beneath this a Person not ugly:

See the frame of life and not its copy.

A peek through the trapdoor is all it takes

To marvel at the hiddenness of this reality.

To a glance or gesture I place all my stakes:

That I am more than this mere triviality!

A person behind a silhouette

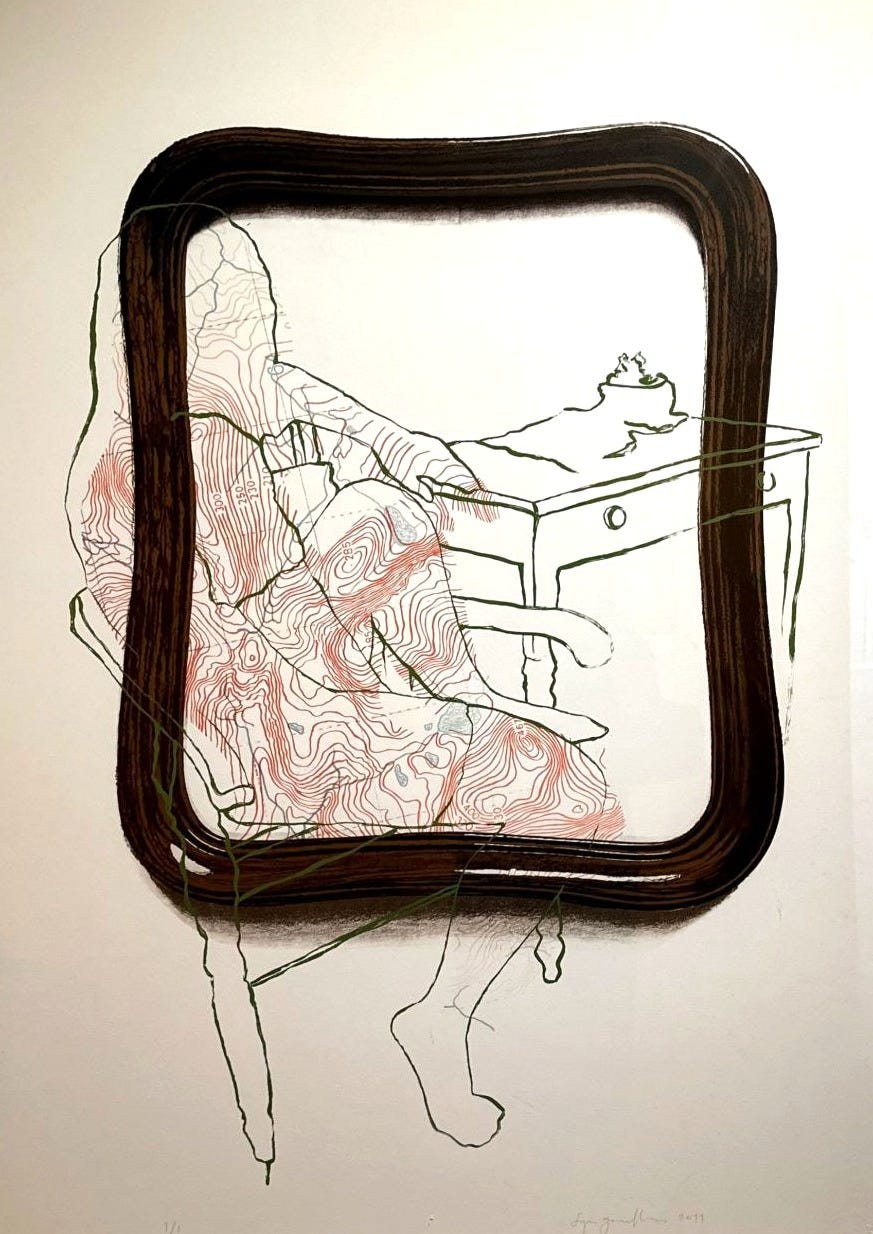

Lyra Abueg Garcellano was recently featured in The Metropolitan Museum of Manila’s exhibit, Chances of Contact: Contemporary Prints from the Philippines and Singapore. One of her works, Trapdoor I, depicts a woman’s silhouette (a characteristic of her anthropomorphic-centered style) comfortably seated.1 In the foreground of the silhouette red lines are firmly imposed, which from a distance might look like veins, but a closer inspection reveals that it is a topographical map with elevation data. An antique-looking frame, too small to fit the subject, is impressed on the figure, allowing portions of the subject’s limbs to protrude and escape from the frame.

Garcellano is keenly aware of “the power of ‘frames’ not only to include, but also to exclude, the artist challenges the notion of a work of art as invulnerable and insular, begging the question of what happens beyond the frame.”2 She makes use of this forceful image, deliberately employing an antique picture frame, to construct a narrative. As the ekphrastic poem above suggests, it may be described as two layers of reality within the work: the reality of the subject and the reality behind the frame; outside these two layers is the reality of the viewer. This easily disorients the viewer and makes it difficult for the viewer to penetrate the metaphysical barriers, the levels of reality, embedded in the artwork. But that’s all part of the point.

On the one hand, the subject is portrayed in a contemplative-like atmosphere. She seems to be pondering while looking outside the antique frame and peers in the reality behind the frame, that is, the reality of how people look at her. The elevation data of the topographic map imposed on the subject are crucial to the narrative that Garcellano paints. In topographical analyses, elevation data are used to determine the contours of a specific terrain, particularly the altitude measured from sea level to a definite geographical point. This permits one to ascertain the degree of a terrain’s slope and height above the sea. Garcellano’s decision to mix this map with the shadowed figure is an unusual creative decision, since most of her subjects are depicted as silhouetted figures plainly filled in white. It is an evocation of “the abstract self in space, emphasizing the manifestation of memories in our projected selves.”3 This abstraction is deliberate on her part, for she trusts “that her objects will be able to convey the larger message she projects.”4

The elevation data pressed onto the figure urges us to make a connection between the subject’s body and the contours of a land area, undoubtedly signifying the shape of the figure’s body—full of creases, folds, crevices, protrusions, and bumps, among others, which all point to one thing: the body’s uneven surface, her disproportionate figure, falling short of the physical expectations of a beautiful body. The work may therefore be taken as a clear critique of feminine beauty standards, which often only take the corporeal condition as the primary criterion, and fail to see the person behind the body. The person behind the body is indeed mediated by a kind of “trapdoor,” hidden from unassuming people; yet behind it is a whole world in itself.5

The inescapable art economy

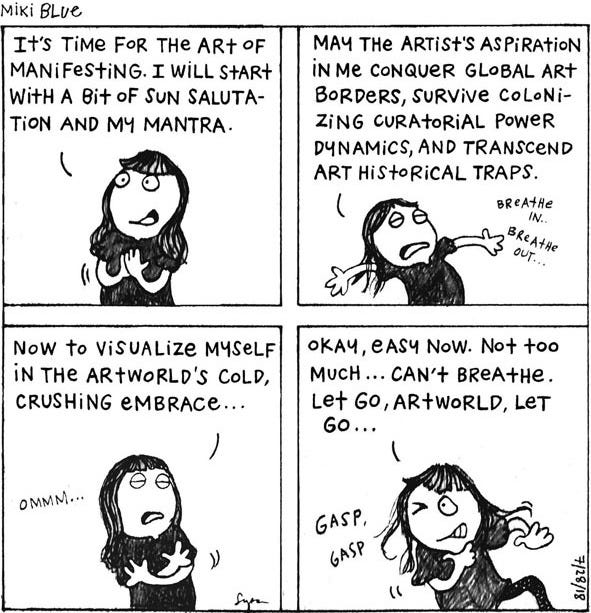

Garcellano’s Trapdoor I is one of the three prints exhibited in Chances of Contact. The other two prints, Temps perdu 1 and Temps perdu 4 employ the same motif of the antique frame and silhouetted figure. Garcellano is not a foreigner to printmaking. She wrote and drew comics, “Atomo and Weboy,” for the Philippine Daily Inquirer six days a week for nearly a decade.6 Her comics, she believed, “was about mapping the prevailing art currencies within an exhibition economy and how a practitioner navigates or negotiates these gatekeeping mechanisms.”7 In any case, even her creative process could be said to imbibe printmaking principles.8 Each stage in the process of Garcellano’s artmaking is imbued with different mediums. Inasmuch as she is a writer, drawing from the literary proclivities she inherited from her family, she first puts into words the ideas she has: “My process always stems from words, because I come from a family of writers. I don’t draw my ideas; I write them down. Then I translate them into things I make” [emphasis added].9 Afterward, she takes photographs of her subjects, mostly women, and then “play[s] with the images on [her] computer.”10

This part is important to her because her subjects are persons whom she comes to befriend and gets to know well. She said that knowing the person who is her subject is part of her creative process.11 She then translates those ideas and images into the canvas when she's ready. Her method employs a mix of words, photographs, and paint. Most of the time, only the final product is seen, and the process the artwork underwent is left hidden from the audience. Apart from the artwork labels identifying the works’ medium(s), there is no other way to discover the lengthy and creative process of making the art.

Regarding the importance of printmaking in the artistic atmosphere, Patrick Flores said: “The medium of print has constantly shifted in Philippine art history from the contexts of cartography to the plays of catechism, from commentary to modern and contemporary art. In every way it turned, the print was responsive to the demands of artistic expression and the urgencies of its social and cultural milieu.”12 Garcellano’s print works exhibited in Chances of Contact, especially her Trapdoor I, are very much reflective of this driving force behind printmaking. Her work is a testament to the innate communicative power of art prints to appraise the contemporary atmosphere of ideas, values, and beliefs.

Although her artworks are greatly inspired by Philippine historical narratives, which she has often depicted with modern twists, they serve something apart from historical aims or a search for a national identity. She’s more concerned about the art ecosystem in which her artworks circulate. Garcellano has had a strong apprehension against the art world, particularly art fairs which, to her, are “traps.”13 She acknowledges that it is almost inevitable that artists have to participate. Artists have to be noticed by an audience, otherwise they do not receive recognition. It’s an inescapable vicious cycle because “if no one sees your paintings, listens to your music, reads your prose, or views your films, then they just steadily cease to exist.”14 She dubbed this unavoidable compromise as “the artworld circus.”15 With great insight (not without some frustration) she said: “In a country where the market and cultural intermediaries are extremely blurred, either artists are oblivious of the complicity of the various institutions, or their awareness is obscured as to how a select few can hold the door ajar for the artists to enter or exit.”16

Furthermore, this particular work of hers, Trapdoor I, is a unique product. Usually, printmade works are reproduced in limited copies. But only one such print of Trapdoor I exists, which is itself a response to the democratic character of printmaking, which Patrick Flores insisted must be taken advantage of and “fully enhanced.”17 Imelda Cajipe-Endaya noted: “Much as printmaking has greatly opened up endless possibilities of creativity and distribution, issues of ethics can be vigilantly corrected and resolved by truthful declaration and efficient documentation.”18

But Garcellano circumvents this difficulty by challenging the very notion of democratizing prints. To quote her at length: “To foster the growth of such practices/movements is to creatively counter the metastasizing of dead ends in art. By diligently identifying, fragmenting and breaking apart the mechanisms that dominate, centralize, and contain—the consequent re-construction and re-ordering can only set in motion what was once conceived as inconceivable. To crack open what has been locked in the long-established or standardized ways of meaning- and art- making is to also open the self and community to decolonized (non-neoliberal) processes of engagement. Such efforts can be cultivated by welcoming practices in non-expected conduits (and comprehending them with non-expected rules). Re-wiring is key. It will take time. And perhaps a whole lot of unfamiliar anxieties, but weathered and generated, not by the will to keep up with the assertions of prevailing historically, socially, and economically accepted inequitable cultural structures, but by a system overhaul.”19

Her artworks, therefore, are also a striking commentary on the decadence of the artworld that forces artists to refrain from experimenting with new styles and methods, and instead coerces them to stick to what will be “accepted” by the commercial market.20 As such, Garcellano chooses to prod art ecosystems and the Philippine historical narratives that intend to nudge the social conscience about these matters. So much so that she “advances an operative form of discourse within a climate of restiveness and dissent.”21 Garcellano’s Trapdoor I is only one such example, but with it, we already get a glimpse of its potency to shake up social change, only waiting to be unleashed.

A short biography of Lyra Garcellano

Lyra Abueg Garcellano is a keen observer of human life and the world inhabited by present man. Born in 1972 to a family of writers, Garcellano was quickly immersed in the world of art. Her literary proclivities, enhanced by her nearly three-decade-long experience as an artist, translated into the publishing of her newest book containing an anthology of essays on art, Elsewhere: Writings on Art, launched this month on October 9 at the University of the Philippines Fine Arts Gallery.22

She completed her Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies at the Ateneo de Manila University in 1994, then obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Studio Arts at the University of the Philippines in 2000. Garcellano finished the degree of Master of Arts in Art Theory and Criticism at the latter university in 2019.

As early as 1998, Garcellano began exhibiting her works in galleries locally and abroad. She was an illustrator for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, creating the comics “Atomo and Weboy,” which lasted almost a decade from 2000 to 2009. Now and then, she posts comics on her Instagram art account, @mikibluetoons, where she often appropriates philosophical allegories and ontologically contentious notions to challenge the artistic and cultural atmosphere in the Philippines. She said, “Comics are another way to talk about what I want to talk about: the pressures and problems in the meaning-making of art.”23

Garcellano has a wide array of thematic interests, but her primary interests lie in the artworld dynamic (particularly the trivialization of artistic value through the art market) and, more recently, Philippine historical narratives. Over the pandemic, she produced works that probed nineteenth-century Philippine politics inspired by Damian Domingo and the tipos del país, which were exhibited in 2022 at the Tall Gallery in Makati City.24

In 2006, Garcellano was awarded the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ prestigious Thirteen Artists Award. The Cultural Center of the Philippines succinctly described her work as characterized by “[s]parseness and formal elegance… [where] aesthetic cannot be detached from the meanings defined by her elements”—an attitude that has consistently configured her work ever since.25

León Gallery, “The Kingly Treasures Action 2015,” León Gallery: Fine Art & Antiques, https://leon-gallery.com/auctions/lot/The-Kingly-Treasures-Auction-2015/172/25

León Gallery, “The Kingly Treasures Action 2015.”

STPI Creative Workshop & Gallery, “Lyra Garcellano,” n.d. https://www.stpi.com.sg/artists/lyra-garcellano/

Cultural Center of the Philippines, Thirteen Artists Awards 2006 (Pasay City: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 2006).

STPI Creative Workshop & Gallery, “Lyra Garcellano.”

Ali Van, “Interview with Lyra Garcellano,” Asia Art Archive in America, May 25, 2010, https://www.aaa-a.org/programs/interview-with-lyra-garcellano and Sam Marcelo, “A comics anthology answers the question: ‘Are people still willing to work for free?’,” BusinessWorld, November 6, 2015, https://www.bworldonline.com/staying-in/2015/11/06/11710/let-me-answer-that-by-asking-you-this/

Vanessa Bicomong, “Questioning the art economy,” Lifestyle Inquirer, February 15, 2021, https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/379139/questioning-the-art-economy/

Cf. Lyra Garcellano, “Comics: A Cultural Tonic,” CoverStory, October 14, 2022, https://coverstory.ph/comics-a-cultural-tonic/

A. Van, “Interview with Lyra Garcellano.”

A. Van, “Interview with Lyra Garcellano.”

A. Van, “Interview with Lyra Garcellano.”

Patrick Flores, “The Strike of Print,” in Tirada: 50 Years of Philippine Printmaking 1968-2018 (Pasay City: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 2020), 7.

Sam Marcelo, “Dissatisfied with the car park, 10 galleries move to convention center,” BusinessWorld, February 5, 2020, https://www.bworldonline.com/editors-picks/2020/02/05/276760/dissatisfied-with-the-car-park-10-galleries-move-to-convention-center/

Lyra Garcellano, “Art Writing and ‘Stilled Lives’,” Cartellino, October 29, 2021, https://cartellino.com/features/2021/10/29/Art-Writing-and-Stilled-Lives

Elizabeth Lolarga, “Lyra Garcellano: Art isn’t easy,” The Diarist, October 10, 2024, https://www.thediarist.ph/lyra-garcellano-art-isnt-easy/

Lyra Garcellano, “Prestige Machines and Performance Anxieties in the Age of the Economy of Recognition,” Ctrl+P Journal of Contemporary Art, no. 19 (December 2019): 51.

Patrick Flores, “The Strike of Print,” 14.

Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, “TIRADA: Potential, Potency & Women Printmakers,” in Tirada: 50 Years of Philippine Printmaking 1968-2018 (Pasay City: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 2020), 28.

Garcellano, “The Age of the Economy of Recognition,” 56.

Sam Marcelo, “Dissatisfied with the car park, 10 galleries move to convention center.”

Cultural Center of the Philippines, Thirteen Artists Awards 2006.

College of Fine Arts, “Lyra Garcellano’s Elsewhere: Writings on Art Book Launch,” October 9, 2024, https://cfa.upd.edu.ph/2024/10/09/lyra-garcellanos-elsewhere-writings-on-art-book-launch/

Bicomong, “Questioning the art economy.”

Finale Art File, “2022 Exhibitions,” https://www.finaleartfile.com/2022

Cultural Center of the Philippines, Thirteen Artists Awards 2006.